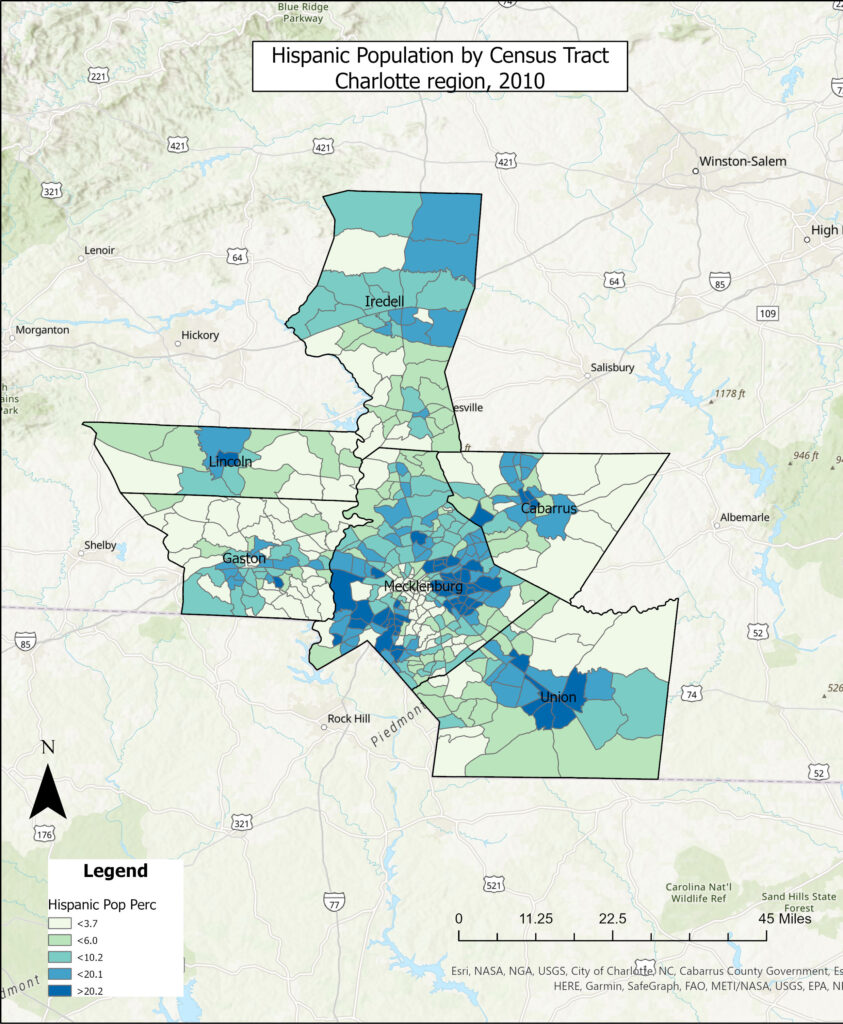

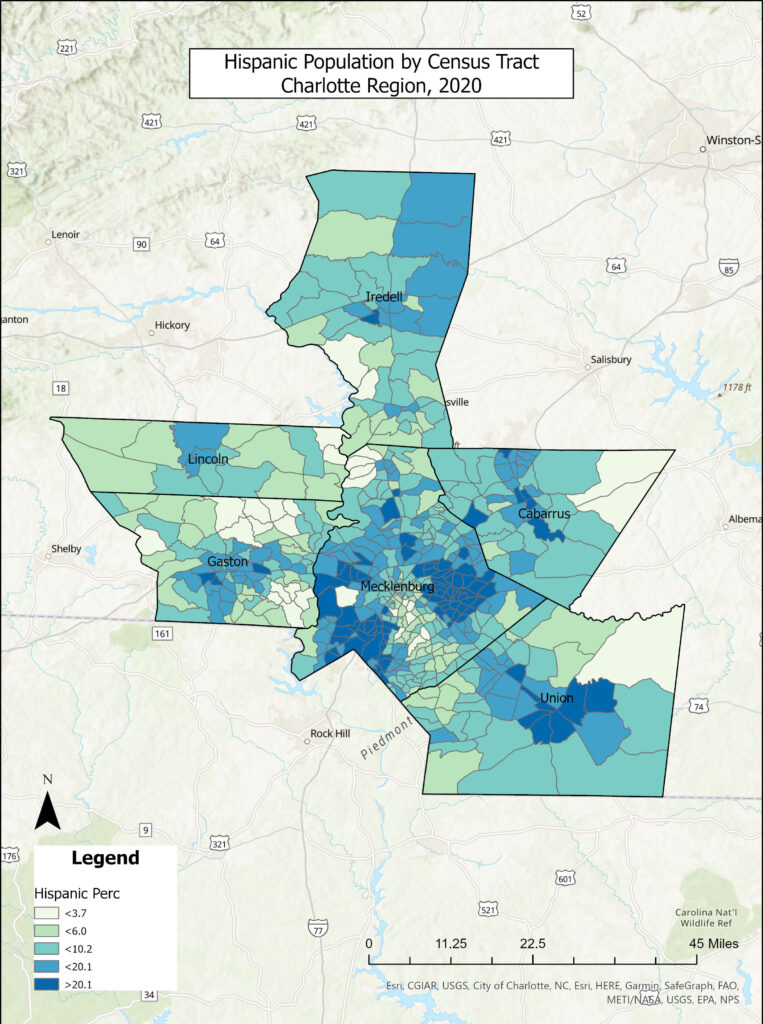

Charlotte and its surrounding Mecklenburg County began emerging as a new migrant gateway by the mid-1990s (Singer, et al. 2008) and has since witnessed one of the highest growth rates of foreign-born populations in the US (Harden et al, 2015). Between 1990 and 2010, the foreign-born population in Mecklenburg County increased by 595% (Furuseth et al, 2015). The majority of those migrants arrive from Latin America. Between 2000 and 2006, the enrollment of Spanish-speaking children in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools increased from 4.5% to 12.2% (Smith, 2007) and these trends continue today. Latin American migrants have followed a non-traditional settlement pattern as they moved into more disparate neighborhoods throughout Charlotte’s suburban landscape (Hanchett, 2013). Two neighborhoods with extensive Latinx placemaking can be found in East Charlotte along Central Avenue and in South Charlotte along South Boulevard. Latinx placemaking is visible in these areas as increasing numbers of Latinx residents enroll in public schools, utilize health and social services, and engage in small-scale entrepreneurship (especially in the food industry).

These placemaking efforts by migrants territorialize urban space each day in ways that create inclusivity for Latinx families, but also produce tensions with other groups who lay claim to those spaces. Along South Boulevard, where this research focuses, new developments of mixed use and rental housing are replacing strip mall and factory landscapes. New apartment buildings and condominiums seek to attract newly arriving millennials working in the financial services industry by providing mixed-use, dense development, alongside mass transit. Anecdotal evidence points to the influx of investment as raising the cost of living and encroaching on the placemaking abilities of migrants. Neighborhoods characterized by single-family homes and apartments where many migrants initially found housing in Charlotte are caught up in waves of gentrification along South Blvd. Migrant-owned and migrant-serving businesses are being displaced as strip malls are demolished to make space for new mixed-use buildings. At the same time, corner stores serving low-income migrants are no longer offering government-support food benefits (such as WIC and SNAP) because they feel the demographic of their customers has changed. These signs of urban restructuring make the South Blvd corridor a particularly illustrative place to study its impacts on migrant outcomes.