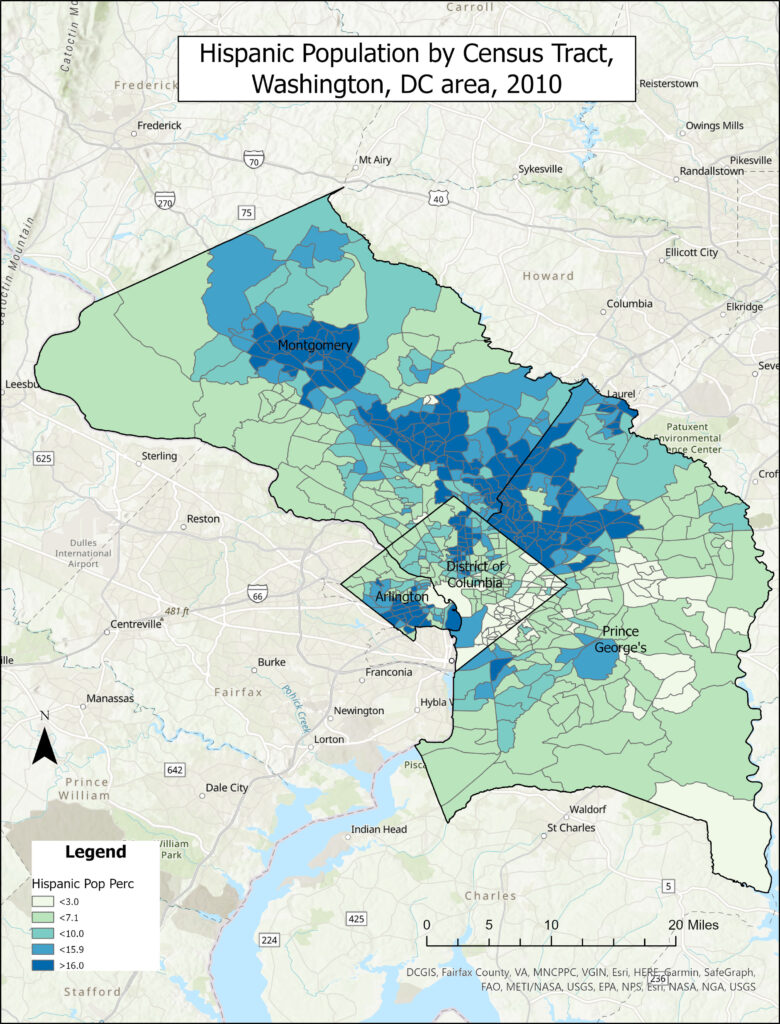

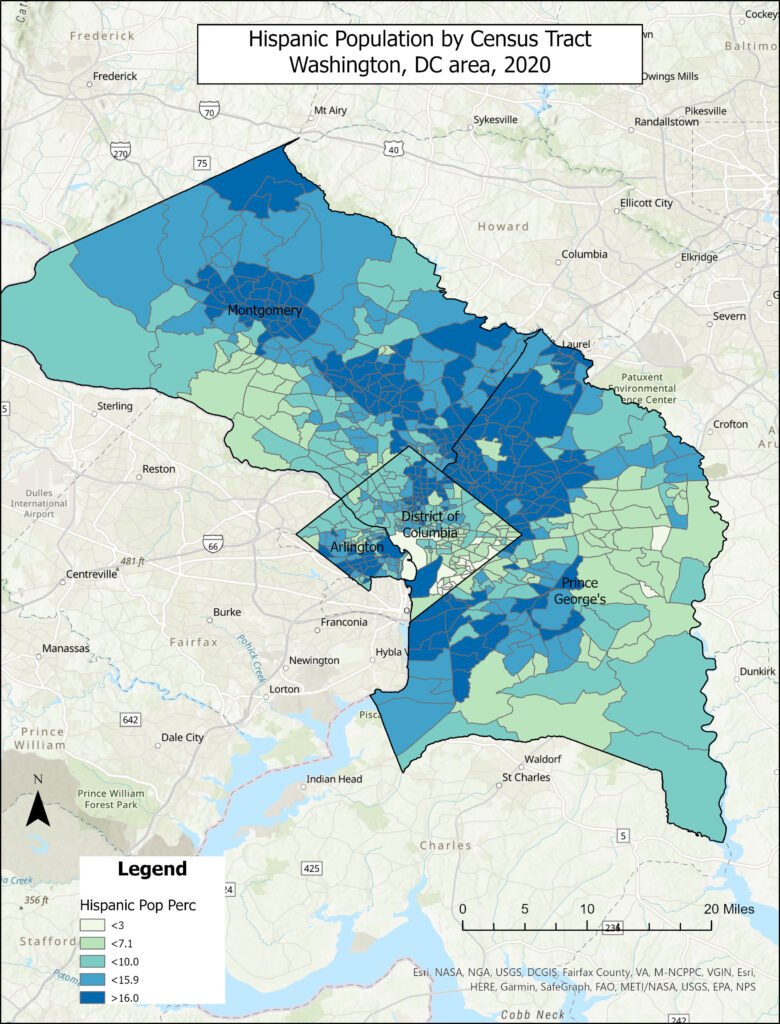

Washington, DC, has experienced a significant influx of migrant residents. The region witnessed some of the greatest increases in migrant population by numerical values in the 2000s – rising from 829,310 in 2000 to 1,223,159 by 2010 (Wilson and Singer, 2010). The majority of those migrants are from Latin America. Historically, Latinxs have concentrated in the Mt. Pleasant-Columbia Heights neighborhood in the northern part of the District (where this research will focus) as well as in neighboring counties in Maryland and Virginia. Yet, the spaces where these residents live and make place are often overlooked in research on DC neighborhoods (Bader, 2016). This data gap reduces the effectiveness of social service provision for residents and businesses (Bird and Danielson, 2016). DC is also experiencing some of the highest rates of gentrification in the country (Shinault and Seltzer, 2019). A 2019 report on American Neighborhood Change found DC to be experiencing the greatest level of gentrification-related displacement among central cities in the country. Approximately 36% of DC residents live in an area that experienced economic expansion alongside low-income displacement since 2000. One prominent site of gentrification in DC is the Mt. Pleasant-Columbia Heights neighborhood.

Following the opening of a subway station in 1999, the area experienced a revitalization in retail and entertainment, now providing more than 1,600 jobs in these sectors (Shinault and Seltzer, 2019). This revitalization also produced significant demographic change with the white non-Hispanic population increasing from 11% in 1990 to 31% in 2010 (Kerr, 2012). Anti-gentrification activists highlight not only the changing retail (and food) landscape, but also the changing culture associated with the area.

Despite these changes, Mt. Pleasant has been heralded by some as an example of how neighborhoods can fight back against gentrification. Morley (2021) tells the story of the neighborhood’s fight against CVS that successfully kept the pharmacy chain out of Mt. Pleasant, providing some stability and hope for several local businesses. Some observers caution that the gentrification debate in DC pays insufficient attention to migrant communities (Baca and Finio, 2018). Mt. Pleasant’s migrant foodscape has thrived, in part, because of the community that has been cultivated among business owners and neighborhood residents. For immigrant-owned businesses in particular, the prospect of gentrification appears distant, and the related outcome of displacement unlikely, given the role their businesses play in attracting new residents.

To understand how the neighborhoods are evolving, we return to DC each year to conduct field surveys, which entails taking pictures of the food businesses in each place to see how they’ve changed over time. Following two full years of data collection in Mt. Pleasant and Columbia Heights, we identified one new business, eleven improved businesses, and two declining businesses out of our total sample of 59 businesses.

New businesses are easy enough to categorize: they weren’t there the previous year and are open now. “Improved” businesses are identified based on visible exterior improvements year-to-year. They exhibit one or more of the following changes:

- Is there new construction on the premises?

- Is there new signage?

- Is there any new paint on the exterior?

- Has the parking lot been improved in any way?

By comparing the present state of a business to photos of it from previous years, we are able to know if any of these improvements have been made and label it accordingly. However, any interpretation of these improvements (i.e. it indicates the business is thriving, it indicates the priorities of the business owner, etc.) is less clear, because we have found that there are instances where the improvements to the infrastructure may not be the doing of the business owner, but the building owner. Such a change may be innocuous, but it could also signal a property owner’s intentions to sell or attract new tenants. Thus, we are careful to avoid making conclusions about the meaning of improvements generally, and instead make assessments on a case-by-case basis.