Gordon Hull / UNCCA lot of the ideas behind this case study derive from Koskela 2011.

1. The Program

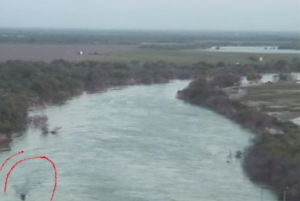

Visit and explore: http://www.texasborderwatch.com/

2. Justification of the Program

The following statement is by Donald L. Reay, executive director of the program:

The following statement is by Donald L. Reay, executive director of the program:

“When someone reports suspicious activity, the message goes to a server, and is then passed on to designated locations, which decide if a response is certified. Designated locations are the sheriffs. In the first 48 hours of the project we had 200,000 alerts. I didn’t see all of them but there was one case, for example, of movement in an isolated area. It was certainly out of the ordinary. This time it turned out that we didn’t find any wrongdoing there. …

If we encounter a person we suspect is undocumented, then we pass them on to the federal authorities. It’s misinformation by our own media to say that we targeting immigration. The reason we’ve set up the system is to sustain our decreased crime rate due to increased patrol numbers.

Of course there are people who will talk about the Big Brother thing, others who will talk about immigration, and others who will say it’s voyeuristic. We know we’ll get criticism. But we know we’re doing this for the safety of the nation. We have a pretty open border with our neighbors to the south and bad people could take advantage of that. I’m sure there’ll be vandalism attempts once they find out where the cameras are. That’s why we’re not telling them where they are! And that’s not infringing on privacy—we’re not looking in people’s windows. These cameras are in wide open spaces where citizens asked for them”

Discussion questions

- What values does Reay claim the Border Watch program upholds?

- Why do those values matter?

- Are there any values that would be undermined by the Border Watch program? Why do those values matter?

3. Politics and images

Koskela writes: “If we take seriously the claims that visual images are political, and that the person using surveillance equipment—in this case, watching the website on her/his computer—does not find knowledge but creates it, we can ask what kind of knowledge an American who is committed enough to do the observation is likely to create. If different audiences provide different readings of same images, what kind of readings are the patriotic Americans likely to give? If the interpretations have both deliberate and unintended consequences, what might these consequences be in the case of the Texas Virtual Border Watch Program?” (55)

- What is the claim that images are political? Explain this, and come up with two examples (not from the Border Watch program).

- What does it mean to say that the person watching “creates” knowledge, but does not “find” it?

- Provide answers to her last two questions.

4. Security and other values

- Is immigration a security problem? Why or why not? Is there a better value or set of values through which to understand immigration?

- Provide a definition of “security” according to which immigration would be a security problem. Then provide a definition of “security” according to which immigration would not be a security problem. Which definition is better, and why?

- Assume for the moment that immigration is in fact a security problem. How does the Texas Virtual Border Watch uphold, or not uphold, the value of security? Is there a better way to achieve the same value?

- Koskela proposes: “an automated computer system would likely be more effective than the Internet site, but it would mediate a very different image. It is essential to provide the anxious public with the impression that they are able to ‘do something’” (60). Assess this statement. What does it say about the possible meanings of “security?”

- Are the issues surrounding Texas Border Watch driven by technology (in other words, is this appropriately categorized as a “technology ethics” problem)? If so, why? If not, why not?

- Do the various motives of the observers (the people who watch at home, and report suspicious activity) matter in assessing the ethics of the program?

5. Sources

Koskela, Hille 2011. “’Don’t mess with Texas!’ Texas Virtual Border Watch Program and the (botched) politics of responsibilization,” Crime, Media, Culture 7, 49-65.