REACH FURTHER. Global Competitiveness Starts Here. (motto on the letterhead of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg, NC public school system)

It is precisely so as to be able to enter into competition with other states. . .that government [has to regulate the life of] its subjects (Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics, 1979:7).

It will be a great day when every prominent leader in higher education exhibits the kinds of creativity and critical thinking skills they laud as necessary for the success of contemporary college students. Sadly, that day has not yet come.

It will be a great day when every prominent leader in higher education exhibits the kinds of creativity and critical thinking skills they laud as necessary for the success of contemporary college students. Sadly, that day has not yet come.

Early this year, for example, former University of North Carolina System president Molly Corbett Broad outlined some of the challenges facing American higher education at a meeting of the University of Wisconsin’s Board of Regents.[1] As the current President of the American Council on Education, a venerable organization which has labored for decades on behalf of higher education,[2] Broad is one of the primary faces of institutional higher education for the worlds of government and business.

And so when she turns to face the governing board of a major state university system, she speaks to them in language of business.[3] Broad outlined a number of trends, beginning with financial and demographic challenges to what she called the “Iron Triangle” of costs, access, and quality.[4] She reminded the Regents that Moody’s Investor Services had just downgraded the whole of the higher education industry because “U.S. higher education is at a critical juncture in the evolution of its business model, [and] even the market-leading institutions have diminished prospects for revenue growth, and most universities are going to have to lower their cost structure.”[5] The strategy of raising tuition “by ever increasing amounts” as has been done since the 2008 recession, is not a sustainable strategy, she said, particularly given the doubling of student debt since 2003, the first year in which revenue from state appropriations for higher education was surpassed by revenue from tuition.

The solution, she proposes, is innovation, including the embrace of MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses), data mining for enhancing student advising and placement, and more flexible certifications of competency. “The belief is,” she said,

“that you can’t increase quality unless you also increase cost. And you can’t expand access without increasing cost. Well, I think that all of that Iron Triangle issue is now being challenged in the face of all of these pressures. And it’s precipitating some very interesting innovations, and advances in the teaching and learning process that come from the advancements in information technology and computer science, and in cognitive science, and in other areas of universities.”

This shouldn’t be surprising, she continued.

“Our universities have been the cradle for the development of these advanced technology ideas, advanced networking capabilities, and when we think about it, it is some of those bright university graduates that went on to develop the companies like Amazon, Google, Facebook, LinkedIn, that have become the companies with the largest market cap[italization] in our country, and I guess we should say, is now the time that some of that expertise developed within the university should now be applied to the university itself?”

It’s a good question. Certainly universities and their graduates develop many wonderful things. Among them are the algorithms that allow us to shop online for Roomba vacuum cleaners or shark costumes for cats, and the software that lets us upload or search for videos of cats wearing those costumes while riding on Roombas, or even doing so while chasing ducklings.

But there are other things created by universities and their graduates–Revenue Center Management,[6] for example, or enhanced interrogation techniques, or napalm— that we might not generally like to see applied to them in turn. Sometimes this is because particular innovations don’t work very well in the university context. Sometimes it’s because these innovations do what they were designed to do, but in pursuit of faulty goals. And sometimes because they’re just altogether bad. One of the problems with Broad’s approach to education is that she is unable to distinguish between ends and means. Another is that she consistently misreads her sources.

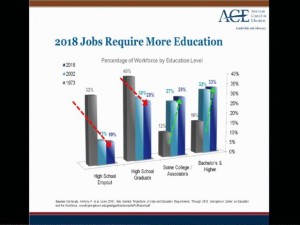

According to President Broad, changing demographics and economic demands require changes to higher education’s “business model.” The growing number of “post-traditional” students who are not 18-22-year olds seeking four year degrees, require an educational experience that can help them improve their skills to compete in a labor market which demands ever higher credentials. Here, education is phrased as a response to students’ need for skills in a changing national economy.

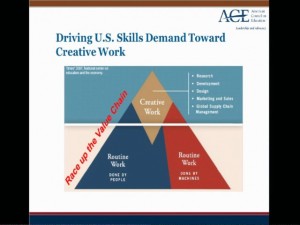

In support of this idea, she cites a study by Anthony P. Carnevale, Nicole Smith, and Jeff Strohl of Georgetown University’s Center for Education and the Workforce,[9] from which the slide shown below was adapted:

Her argument is that this chart shows that long-term shifts in the economy are creating more and better jobs in highly-skilled occupations, sparking a “race up the value chain” away from physical and routine tasks toward creative work in occupations such as research, development, marketing, and design. The lesson is that we need to produce more college graduates lest those positions go unfilled.

Her argument is that this chart shows that long-term shifts in the economy are creating more and better jobs in highly-skilled occupations, sparking a “race up the value chain” away from physical and routine tasks toward creative work in occupations such as research, development, marketing, and design. The lesson is that we need to produce more college graduates lest those positions go unfilled.

(As an aside, Broad appears to have misread the report on education and international economic competitiveness from which her “value chain” illustration was taken. Published by the New Commission on the Skills of the American Workforce in 2007, it dealt largely with revolutionizing the K-12 system, and recommended exactly the opposite of what she and most state political leaders are interested in, which is cutting costs above all. For example, rather than reducing resources for early childhood education, as has been the trend in most states, the report recommends full support for universal pre-Kindergarten programs. And rather than the “college for everyone” approach shared by everyone from President Broad to President Obama, it recommends well-designed high-school vocational tracks that will put skilled workers into the marketplace by age eighteen.[10])

(As an aside, Broad appears to have misread the report on education and international economic competitiveness from which her “value chain” illustration was taken. Published by the New Commission on the Skills of the American Workforce in 2007, it dealt largely with revolutionizing the K-12 system, and recommended exactly the opposite of what she and most state political leaders are interested in, which is cutting costs above all. For example, rather than reducing resources for early childhood education, as has been the trend in most states, the report recommends full support for universal pre-Kindergarten programs. And rather than the “college for everyone” approach shared by everyone from President Broad to President Obama, it recommends well-designed high-school vocational tracks that will put skilled workers into the marketplace by age eighteen.[10])

Actually reading the Carnevale report on the changing economy shows something different from massive change in the kinds of jobs available. According to the authors, two-thirds of the upward movement in educational requirements needed for future jobs is not due to shifts in the structure of the job market, but to the phenomenon of “upskilling,” in which the educational requirements listed for particular positions increase whether or not there have been actual changes in the skills required for them.[11] Although one element of upskilling may be the need for more skills in given categories of “traditional” employment such as auto mechanics, another large part is the increasing preference of Human Resources managers for filling even the most menial jobs with college graduates. This “up-credentialling” is independent of the actual need for more skills, and is the result of a poor economy as well as of the notion that college graduates are a better fit for their firms. In the words of one prominent Atlanta law firm’s managing partner, people with college degrees “are just more career-oriented. Going to college means they are making a real commitment to their futures. They’re not just looking for a paycheck.”[12] Going to college also tends to be unevenly distributed in the U.S., meaning that college graduates are far less likely to be ethnic minorities or members of the working class. Up-credentialling is a barrier to economic mobility that pretends that structural inequalities are actually the result of personality shortcomings in those without degrees.

In any case, the lucky new graduates’ commitment to their jobs as file clerks and couriers may be due more to the fact that they are quite likely to be so deeply in debt from student loans that they need a steady income source to avoid the legal complications of loan default. Interested in their paychecks every bit as much as young people without college degrees, they are more likely to remain underemployed and increasingly willing to work longer hours or under worse conditions for no additional compensation in order to keep their jobs. Contrary to Broad’s reading of Carnevale’s research, “The supply of jobs requiring college degrees is growing more slowly than the supply of those holding such degrees. Hence, more and more college graduates are crowding out high-school graduates in such blue-collar, low-skilled jobs as taxi driver, firefighter, and retail sales clerks.”[13]

Of course the financial crisis, the changing economy, and the demographics of our student body are not our only challenges as educators.

We just don’t seem to be doing a very good job altogether.

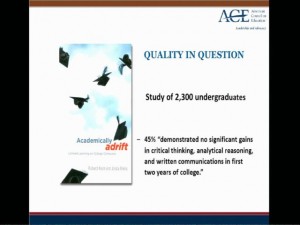

Broad repeated Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa’s shocking claim, in their 2011 sociological study Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses (University of Chicago Press), that 45% of American college students make no significant gains in critical thinking skills in their first two years of college, an indication that our system of higher education has a quality crisis as well as a financial one.

“The evidence suggests,” President Broad told the Wisconsin Regents,

“that we are not meeting the traditional goals [of higher education] very fully, those goals of developing a broad range of intellectual skills, specialized knowledge in the major areas of a student’s concentration, a demonstrated ability to communicate in writing their knowledge and their ability to apply that knowledge in a real-world environment. . .We must do a better job of deepening learning and enhancing these results.”

Regrettably, the President of the American Council on Education again seems to have little understanding of the meaning of the data she presented. Despite the publicity surrounding Academically Adrift when it was first published—a notoriety due almost entirely to the ease with which the titillating 45% intellectual stagnation figure could be quoted in condemnation of higher education as a whole—the book employs all of its sophisticated statistical analyses of the sexy new Collegiate Learning Assessment instrument[14] in order to tell us exactly nothing that we haven’t known for decades. If we assume, for the sake of argument, that their CLA data are meaningful and their methodology is sound, here is what Arum and Roksa say:

First, higher education reproduces existing social inequalities (p. 40). Students whose parents have graduate and professional degrees perform better on the CLA than students whose parents didn’t graduate from high school (p. 38). White students score higher on the CLA than minority students (p. 39). Students with better academic preparation coming out of high school perform better on the CLA than students whose prior educational experience was poor (pp. 44-47). Students from socioeconomically disadvantaged households don’t perform as well on the CLA as students from privileged family backgrounds (p. 44). Students who attend highly selective colleges perform better on the exam than students who attend less selective colleges. These different sorts of inequalities overlap in complex ways.

However, the top achievers on the CLA instrument come from all kinds of backgrounds and attend all kinds of institutions. What accounts for learning success if we control for the effects of background and preparation? Unsurprisingly, students who work hard at academic tasks end up doing better on this test of academic skills than students who do not. Those who meet with faculty outside of class, and who spend a lot of time studying perform better than students who have little contact with faculty outside of class, and who engage in nonacademic extracurricular activities. In the end, Arum and Roksa found, the single most important factor increasing performance on the CLA was high faculty expectations. Controlling for all other background characteristics and college activities, students who report having taken classes which demand more than forty pages of reading per week, and requiring more than twenty pages of writing during the semester, are those who make the most progress on the CLA’s test of critical thinking and analytical writing skills (pp. 93-96, 115, 119, 122, tables A3.3, A4.1, A4.5).

The hysterical, uncritical, and uninformed media coverage of Academically Adrift repeated the 45% intellectual stagnation figure over and over as if it were the book’s most significant finding. For Arum and Roksa, though, it was this 40/20 standard—forty pages of reading per week and twenty pages of writing per semester—that was repeated again and again as a model of effective and proper academic practice. Despite the overwrought title of their book, the focus was not on the failure of higher education, but on identifying what kinds of college experiences lead to success. What leads to success, in the end, all other things being equal, is students reading and writing a lot.

Now, when one thinks of the kinds of institutions that provide freshmen and first-semester sophomores the opportunity for intensive reading and writing experiences (Arum and Roksa’s data measure only progress made during the first three full semesters of college (p. 35)), one immediately thinks of relatively small and selective institutions, the kind which often very purposely require students to take at least one small writing-intensive seminar class in their first few terms. One thinks of institutions which have the financial resources, the teacher-student ratios, and the admissions policies necessary to make this happen. And then it seems a wonder that as many as fifty-five percent of new college students do make significant gains in CLA scores in their first three semesters. In the highly stratified environment of American higher educational institutions, the vast majority of students have no such opportunity.

In the end, Broad’s presentation brings to mind former Secretary of State Colin Powell’s regrettable PowerPoint presentation to the United Nations in February 2003, in which he argued for the need to invade Iraq. Both of them tried to claim that the data speak for themselves. But one of the elements of critical thinking is the recognition that data never speak for themselves. They are produced and interpreted by individuals and groups with interests to further.

We need academic leaders at the national level who embody the intellectual skills they praise in their speeches. We need academic leaders who will stop telling the political and business elites who fund and who serve as trustees of American universities only what they want to hear: that we can always do more with less by buying more computer software, or that we are committed to producing a cadre of engineers so vast that they will be willing to compete on price with their Chinese and Indian competitors. We need leaders who will tell the truth: that education is not merely about jobs. That not everyone needs to go to college. And that when they do, instilling critical thinking skills, or cultural literacy, or an appreciation of diversity, or a firm grasp of chemistry, or international experience, or a meaningful engagement with the idea of citizenship; anything really worth knowing, in fact, let alone the nurturing of any real creativity with respect to any of them, are extraordinarily labor-intensive enterprises that cannot be furthered on the cheap. Not even with the very best data-mining software or cognitive science that money can buy.

Notes

[1] The address was titled “Higher Education at a Crossroads: Multiple Challenges, Leadership, and Innovation.” See Sara Goldrick-Rab’s commentary on the address, “The Higher Education Lobby Comes to Madison,” in the Chronicle of Higher Education. For an amusing survey of general trends in “education reform,” see http://www.insidehighered.com//blogs/just-visiting/my-idea-higher-ed-reform-do-nothing .

[2] Among countless other activities, the ACE participated, for example, in formulating and commending to its member institutions the American Association of University Professors’ 1966 Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities, which outlines the primary authority of faculty in decisions about academic issues.

[3] Like the governing boards of most universities, the UW system is overseen largely by bankers, insurance executives, corporate lawyers, and others who represent industries such as telecommunications, real estate developers, oil and gas interests, and so on. They are talented and successful industry leaders and power brokers, and they sometimes define themselves as such, e.g. the UW Regent who announces in his corporate profile that he has “a proven track record of introducing international and local entrepreneurs to federal, state and local leaders. These introductions allow his clients to gain a foothold and collaborate directly with these leaders” (p. 5). Given this fact, why would the leader of the ACE spend her time in front of the Regents simultaneously bemoaning the financial crisis and spinning happy-talk about doing more with less, rather than encouraging them to use their self-proclaimed political influence to increase state funding for a legendary university system?

[4] I had always been taught that an interrelated set of components in which change to one precipitated changes in the others was called a system, but what do I know. The phrase “iron triangle” seems to have been derived from political science, where it is widely used to describe the relationship between government bureaucracies, interest groups, and Congress. Its use with regard to higher education can be found discussed in a 2008 report by The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, “The Iron Triangle: College Presidents Talk About Costs, Access, and Quality.”

[5] See my previous post, “College Costs and Conflicts of Interest.”

[6] See the story of RCM’s application at the University of Southern California in chapter 6 of David L. Kirp’s useful book Shakespeare, Einstein, and the Bottom Line: The Marketing of Higher Education (Harvard University Press 2003).

[9] Carnevale, et. al., Help Wanted.

[10] This chart comes from a 2007 report, Tough Choices or Tough Times,” by the New Commission on the Skills of the American Workforce.

[11] Carnevale, et. al., Help Wanted, p. 127. See Paul Krugman, “It’s Been a Rich Man’s Recovery,” 14 September 2013.

[12] Catherine Rampell, “It Takes a B.A. to Find a Job as a File Clerk,” New York Times 19 February 2013.

[13] See Richard Vedder, Christopher Denhart, and Jonathan Robe, “Why Are Recent College Graduates Underemployed? University Enrollments and Labor Market Realities.”

[14] For more on the CLA, see my earlier post, “Best Practices for Student Assessment.”