19 August 2014

Invited address as the President of the UNC Charlotte Faculty.

UNC Charlotte Faculty and Staff Convocation

Thank you, Chancellor Dubois, for the kind introduction, and for the opportunity to talk a bit about the Faculty agenda this year.

I took my first anthropology class thirty-five years ago this semester, as a freshman in college. And in the long time since then I’ve learned a lot, and have come to some conclusions about human beings, the most important of which is this:

People are nuts.

Don’t get me wrong; one on one, most folks are delightful. But when you put us together in groups, bizarre things happen. We come to take so much for granted as normal, that we lose sight of the fact that in our daily lives we often strive after contradictory goals. Sometimes those contradictions come together in ways that let us see them again for what they are, and these are opportunities to see our culture at work. For example, at the very beginning of last April’s Faculty Council meeting, the UNC Charlotte faculty presented a well-deserved formal commendation to Athletic Director Judy Rose and Coach Brad Lambert, for their outstanding implementation of our new football program. The consensus was that it just could not have been done better. But later on in that same meeting, Dr. Robert Jones, a sports physician and the Director of our Student Health Center, talked to the faculty about the problem of Traumatic Brain Injury among our students, pointing out that even minor concussions can inhibit learning for days or even weeks.

So here we are, a university that wants our students to learn, but at the same time we systematically–and enthusiastically–expose some of our students to the possibility of Traumatic Brain Injury, which inhibits their learning.

Now, this is not a criticism of football. Football is an honorable American cultural institution, and an important feature of the collegiate experience. As a demonstration of skill and strength and masculinity, football is certainly no more strange than the traditional Afghan sport of buzkashi, a mounted game in which riders compete over the possession and movement of the carcass of a goat. Really the strangest thing about football, when you think about it in comparative context, is that it has nothing at all to do with goats and revolves instead around the possession and movement of a small bundle made out of fragments of the carcass of a cow.

Our pursuit of incompatible goals is not a new problem, and it’s not an American problem. People have been doing this for more than ten thousand years, and it happens everywhere.

In Middle Eastern folklore, there are dozens of stories about a character who goes by different names in the Persian, Turkish, and Arabic traditions. In Arabic-speaking countries he’s usually known as Juha or Goha.

In my favorite story, Juha is going with his young son–the cutest little five-year old boy you’ve ever seen–to the market. Juha is riding on his donkey, and his son is walking along beside. They pass a group of people, and Juha hears them whispering–“Oh, what a heartless man! How can he ride on that donkey while his poor little boy walks in the dust? What a bad father!” Juha is embarrassed, so he gets down off the donkey and lifts his son onto its back instead. They continue on, but when they pass another group of people, Juha hears them scoffing– “What is that man doing, walking along while his son rides on that donkey like a spoiled prince? How is the boy ever going to learn respect for his elders?” Juha blushes, and decides that it would be best if they both walked. So he takes his son down from the donkey and they both walk along beside it. But after a little while, people start to laugh–“What idiots! Here’s this fine strong donkey, and these lamebrains walk in the heat rather than riding on it!” Juha, realizing how foolish this is, climbs back up on the donkey and pulls his son up in front of him so they can both ride. But then the people scold–“What a monster! Can’t that man see that his poor donkey is overburdened with two riders? It’s about to collapse! How can he be so cruel?” And so poor Juha sighs, and does the only thing left to do. He dismounts along with his son, and then Juha ducks down and heaves the struggling animal up onto his shoulders, and stumbles off toward the market carrying the donkey, while the whole crowd jeers at how stupid he is.

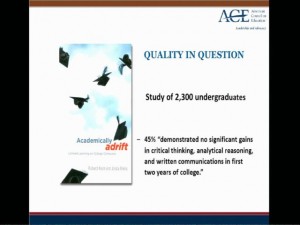

Juha is the perfect model of the university. No matter what he does, it’s just not right. Here at the university, the problem is that we’re too easy on students, and they learn nothing. The problem is that we’re too hard on students, and they flunk out. The problem is that we teach them irrelevant nonsense, and so they’re unqualified to find jobs. But the problem is that we concentrate far too much on job training, instead of teaching critical thinking skills, which are much more important. Universities fail because they refuse to concentrate on teaching the enduring western cultural heritage, and instead they latch onto every passing intellectual fad. But the problem is that universities are stodgy and risk-averse, and too slow to change.

And because we obviously don’t know what we’re doing, we need to be held accountable, so we’re told to measure our productivity and write regular assessments of what we’ve done and what students have learned, in order to prove that we’re actually earning our pay, and if what we do is not readily reducible to numbers and formal rubrics, then maybe we just need to change the way we work so we can generate the right kinds of records.

We’ve picked up the donkey, and we’re staggering under its weight.

So here’s what I hope we can all do this year. I’d like us to take some time to think about how to put down the donkey.

In the past two years, at least four different College Deans at UNC Charlotte have requested full-time EPA staff positions to deal just with the burden of assessment, and it keeps coming. In addition to those we already have, we’re about to get more accountability requirements from General Administration. We’ll be implementing a state-mandated test of critical thinking skills, and working out a new post-tenure review process which will require every tenured faculty member to develop a five year career plan with specific benchmarks that her chair can key to the annual review process. And the Deans will be responsible for evaluating and approving these plans, too. And everyone involved in the process will be required to undergo special training. And the Provost will have to certify that the procedure is being followed properly across campus.

But the more effort we spend on assessing ourselves, the less genuine productivity we have to assess. The more reports we are told to write, the less efficient we become. And I would argue that every new reporting process imposed on the university from the outside is a theft. It’s a theft from you, a theft of your time and attention. It’s a theft from our students. It’s a theft from the progress of our disciplines; it’s a theft from our leaders and from our talented professional staff all the way from administrative assistants and department chairs to the Provost and the Chancellor. It’s a theft from the people of the State of North Carolina.

The job of the faculty is to do four things:

To discover

To create

To teach

To serve.

Faculty Council will have its normal load of decisions to make about bread-and-butter policy issues this year, its normal load of reviewing new curricula and student credit hour requirements, and so on. That won’t change. But this year I would like to provide the Faculty Council with the time and the opportunity to talk with each other about how to put down the donkey that’s been forced onto our shoulders. Working together with Provost Lorden, with college Deans, and with other members of the UNC Charlotte community, in fact with all of you here, staff and students and faculty, I hope we can find ways to lighten the great braying load that is weighing us all down and hampering the university’s ability to do those four central things: to discover, to create, to teach, and to serve.

Because together, those four activities are unique to the university; together they are things that the state cannot do; they are things that NGOs and churches cannot do; they are things that corporations and markets cannot do. And for all their inconsistencies, they are in the end what we as a university have to contribute to humanity.

Let’s all have a good year doing just that. Thank you.

Gregory Starrett, UNC Charlotte Faculty President 2014-2015