Everything Possible and Nothing True: Notes on the Capitol Insurrection, with Joyce Dalsheim. Anthropology Today 37(2):26-30. April 2021.

ABSTRACT: On 6 January 2021, an overwhelmingly white, Christian mob stormed the US Capitol building in Washington DC as part of a rally to ‘Save America’. Moving beyond media reports and the analyses of popular pundits, the authors provide an ethnographic outline of some of the complexities and contradictions on display that day. Thinking with Hannah Arendt, Emmanuel Ladurie, Ursula LeGuin and others, these notes frame the rally preceding the attack on the Capitol in terms of historical narrative, carnival aesthetics and Christian symbolisms of salvation. The rally and attempted insurrection displayed multiple social and symbolic inversions, combining yearnings for order and stability with parody, playful optimism and violent threat. Unlike many other pre‐Lenten carnivals, here it was never entirely clear which social order was being overturned and which was being reinstated, one result of the deeply divided world views that currently characterize much of the US population.

We appear to have been the only anthropologists–perhaps the only social scientists–at the rally that day. The article can be accessed through the Wiley Online Library by itself, or through the April 2021 issue.

*****

Time and the Spectral Other: Demonstrating Against ‘Unite the Right 2’, with Joyce Dalsheim. Anthropology Today 35(1):7-11. February 2019.

ABSTRACT: Recent public protests against right-wing politics in the United States have often demonstrated a sense of surprise at the recurrence of racist, anti-Semitic and fascist ideologies and movements which ought to belong to the past. Using insights from Walter Benjamin, Johannes Fabian and Jacques Derrida, we analyze the recent gathering of thousands of counter-demonstrators at the ‘Unite the Right 2’ rally in Washington, DC and discuss how political and moral enemies are rhetorically consigned to another time. The temporality on display at this demonstration was more complex than linear, progressive time. Instead, it consolidated events from the past, present and future into a sense of eternal and recurrent victory. We argue that this temporality is an expression both of Derrida’s ideas about spectrality and Tanya Luhrmann’s analysis of the moral psychology of faith.

The article can be accessed through the Wiley Online Library by itself, or in the context of Anthropology Today‘s special issue on populist movements .

*****

The Varieties of Secular Experience, published in Comparative Studies in Society and History 52(3):626–651, July 2010:

The Varieties of Secular Experience, published in Comparative Studies in Society and History 52(3):626–651, July 2010:

EXCERPT: “Taking the Egyptian case as an example, this article examines secularism (and its cognates secularity and the secular), not so much as a failed social project, but as a problematic concept. Reflecting on the on-going scholarly interest in the notion of waning secularity in Egypt, I will suggest that the idea reveals as much about the scholars studying it as it does about a changing social world. Building on the work of British philosopher W. B. Gallie, I will argue that secularism is an essentially contested concept, its meanings fluid, variant, and elusive. This is not merely to observe, as many others have done, that “the ‘religious’ and the ‘secular’ are not essentially fixed categories” (Asad 2003: 25), or that “the secular” is so difficult to grasp directly that “it is best pursued through its shadows, as it were” (ibid.: 16). It is to say that the secular’s unfixedness is one of its essential features, and that its significance, therefore, is a function of the arguments it generates and the conflicts it organizes, rather than of some phenomenon it purports to describe. Two things follow from this. The first is that the secular’s usefulness as an analytical concept is deeply suspect. The second is that growing scholarly interest in studying the secular—Michael Warner (2008: 609) writes about “the emerging realm of secular studies” on the model of religious studies—is a phenomenon that requires our attention.”

Link to the full text of this article: Varieties of Secular Experience

The issue of CSSH in which this article appeared was featured on the Social Science Research Council’s blog The Immanent Frame, here.

For a 2024 update on the legendary CSSH “non-special issue” on secularism and further thoughts about the state of “critical secularism studies,” see the conversation here.

*****

Islam and the Politics of Enchantment, published in the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 15: S222-S240 for May 2009, in a special issue, Islam, Politics, Anthropology, edited by Benjamin Soares and Filippo Osella:

ABSTRACT: The North American public sphere is suffused with claims and counterclaims about the relationship between Islam and violence. Schools and publishers have responded with training programs for teachers and curriculum units for students introducing them to the Middle East and its dominant religious tradition. Such programs are often accused by local parents and national intellectuals of pandering to Muslim sensitivities by whitewashing distasteful historical events and even proselytizing young people. Focusing on a 2002 lawsuit filed against California’s Byron Union School District, by parents upset by a classroom role-playing exercise on Islam, this article argues that political fears about terrorist infiltration into U.S. society are building on powerful emotional and cultural concerns about the nature of ritual and the spiritual safety of children exposed to information about other religions. By encouraging public education as a response to political and cultural tensions, educators may in fact be heightening the public’s concerns about Islam as a comprehensive threat.

Link to the full text of the article: Islam and the Politics of Enchantment

The definitive version of the article is available from JRAI at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2009.01551.x/abstract

This special issue of JRAI was published in book form by Wiley-Blackwell in 2010. For more information, see http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1444332953,descCd-tableOfContents.html

*****

Seeking the Seeker: Frameworks for Understanding Islamic Commodities, published in Sophia AGLOS News (Sophia University, Tokyo, Japan) in symposium-based theme issue, Consuming Religion: Globalization and Popular Beliefs issue 9 (2007), pp. 21-26.

Seeking the Seeker: Frameworks for Understanding Islamic Commodities, published in Sophia AGLOS News (Sophia University, Tokyo, Japan) in symposium-based theme issue, Consuming Religion: Globalization and Popular Beliefs issue 9 (2007), pp. 21-26.

EXCERPT: Contemporary Muslim criticisms of the commodification of religion “are similar in some ways to the sociology of culture formulated by members of the Frankfurt School of the mid-twentieth century, particularly Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, as inspired in part by Walter Benjamin. Following Marx, these theorists reflected on the effects the mass production and distribution of commodities might have on the world of culture, particularly the fine arts. They argued that the commoditization of art destroys the “aura” of a work, its uniqueness and authenticity as a singular creation tied to a specific place and time. The mechanically reproduced work of art loses its use value–its ability to draw the viewer out of himself in contemplating it–and becomes mere exchange value, something that can be acquired and displayed, like an item of clothing or other commodity that might mark the buyer’s interest or taste or wealth.”

This issue is not online, so you’ll have to read the full text of Seeking the Seeker here.

*****

The American Interest in Islamic Schooling: A Misplaced Emphasis? published in Middle East Policy, vol. XIII, no. 1 (Spring 2006), pp. 120-131.

The American Interest in Islamic Schooling: A Misplaced Emphasis? published in Middle East Policy, vol. XIII, no. 1 (Spring 2006), pp. 120-131.

EXCERPT: “Rewriting books is easier than changing fundamental social, economic and political institutions with powerful constituencies. . . .Curriculum reform without the reform of infrastructure, political participation and economic opportunity will do nothing to stem internal and external conflicts that do far more than schools to create violent motivations. The doomed economy of petroleum, the patriarchal authority structures of rural villages, the brutality of the Saudi religious police, the legal persecution of Egyptian homosexuals, the abuse of Iraqi prisoners by American soldiers, targeted assassinations by Algerian paramilitaries or by Israeli pilots in American helicopters. . .have far more influence over the political consciousness of children and youth than does anything taught in school, religious or otherwise.”

Read the article here: American Interest in Islamic Schooling

Visit Middle East Policy: http://www.mepc.org/journal or http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/journal.asp?ref=1061-1924

*****

Violence and the Rhetoric of Images, published in Cultural Anthropology 18(3): 398-428, August 2003:

Violence and the Rhetoric of Images, published in Cultural Anthropology 18(3): 398-428, August 2003:

EXCERPT: “This article is about the politics of visual representation, specifically about how the documentary photograph can be used to mobilize collectivities. Images become the medium for transnational political contests in which opposing groups mobilized by projecting onto those images fundamental values: purity versus idolatry, heritage versus fanaticism, injustice versus innocence, cynicism versus responsibility. . . . Documentary newspaper photographs act as a discourse of emotional engagement through which the Egyptian state seeks to assimilate itself with the newspaper reading audience into a single rhetorical subject. By representing emotions visually, photojournalism engages the passions of a diffuse audience and expresses that engagement as a spontaneous unified outpouring of feeling. It becomes in effect the expressive art of the modern political order.”

Link to the full text of this article here: Violence and the Rhetoric of Images

The editors of Cultural Anthropology have assembled supplementary material for this article, including images and questions for class discussion, at http://www.culanth.org/?q=node/233

*****

Who Put the “Secular” in “Secular State”?, The Brown Journal of World Affairs, vol. VI, Issue 1 (Winter/Spring 1999), pp. 147-162.

Who Put the “Secular” in “Secular State”?, The Brown Journal of World Affairs, vol. VI, Issue 1 (Winter/Spring 1999), pp. 147-162.

EXCERPT: “In this essay I hope to add an anthropological voice to the conversation about political Islam, one which seeks its context not in relation to some underdefined “non-political” or “traditional” or “pure” Islam, whatever those might look like, but in a rather more general consideration of the nature of religion and politics. . . .[T]he standard Western understanding of genuine religion as a universe of calm personal devotion, universal harmony, and spiritual development is ethnographically exceptional and historically recent, even in Europe. Moreover, it obstructs our understanding of confessional violence in the modern world by leading us to believe that religion, in its

essential core, is about individuals rather than groups, and about gentleness rather than force. . . . I hope to show three things: first, that religion is, always and everywhere, an inherently political enterprise. Second, that all political projects have central symbolic and ritual dimensions, and thus cannot automatically be distinguished from religion. . . . And finally, that “political Islam” as a label for oppositional or revolutionary groups blinds us to the more pervasive involvement of religion in the constitution of modern states, both in the Middle East and elsewhere. . . . Despite—or perhaps because of—the important role played by ritual processes in modern political and nationalist projects, during the historical development of the nation-state there has been increasing pressure on religious

traditions to assimilate to the Protestant model that belief, rather than ritual practice, is the core of religion. In the nation state, “freedom of religion” is possible only to the extent that religion is held to be an internal, private and personal relationship with the divine rather than a publicly manifested set of social, ritual, or political duties.”

Read the article here: Who Put the “Secular” in “Secular State”?

Visit The Brown Journal of World Affairs at: http://www.bjwa.org/

*****

Signposts Along the Road: Monumental Public Writing in Egypt, Anthropology Today 11(4): 8-13, August 1995.

EXCERPT: “Studies of writing in developing societies generally focus on book, newspaper and commercial literacy, and do not address the cultural significance of writing on craft and manufactured objects, on the one hand, and the use of writing on public signs, murals and billboards, on the other. Although ‘scattered’ indeed, the two latter genres of writing are important. They are also quite similar in their social roles, for although commodities circulate between public and private space, and public signs form relatively permanent parts of the built environment, both are manufactured displays which use writing in exaggerated form, and act simultaneously as geographical and identity markers, art, and foci of ritual acts. Given the centrality of written texts to the theology and practice of Islam, and also the importance of calligraphy in the visual art of the Islamic world, it is surprising that not much attention has been paid to these alternative uses of the written word. Thus I would like here to examine a specific subset of written culture in urban Egypt: the use of monumental writing in public space.”

Read the article here: Signposts Along the Road

*****

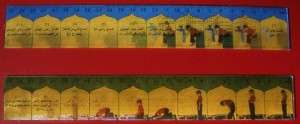

The Hexis of Interpretation: Islam and the Body in the Egyptian Popular School, American Ethnologist 22(4): 953-969, November 1995.

ABSTRACT: This article examines how travelers, colonial officials, and educators have treated prayer and other body rituals in Egyptian popular schools. Once the object of

colonial critiques of indigenous pedagogy, body ritual has now become the focus of a functionalist discourse that reads bodily postures and movements as natural manifestations of social, ideological, and cosmological structures. Starting from Bourdieu’s notion of hexis, the literal embodiment of ideology, the article examines how Egyptians—and anthropologists—extract meaning from ritual behavior.

Full text here: Islam and the Body in the Egyptian Popular School

*****

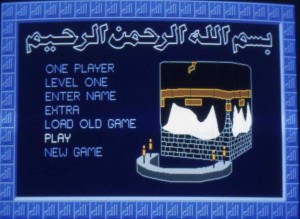

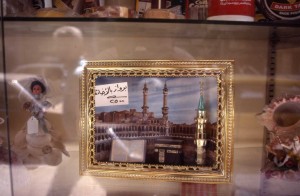

The Political Economy of Religious Commodities in Cairo, American Anthropologist 97(1): 51-68, March 1995.

The Political Economy of Religious Commodities in Cairo, American Anthropologist 97(1): 51-68, March 1995.

ABSTRACT: Anthropology’s rediscovery of material culture has emphasized the centrality of objects and their production in constituting human experience. In Egypt, the design, mass production and marketing of different classes of religious objects-from prayer beads and bumper stickers to children’s board games and jigsaw puzzles-not only construct boundaries between social groups but create alternative ways of understanding and participating in the Islamic tradition. This article explores the distribution and consumption of Islamic paraphernalia, examining how the development of a mass market in religious consumer goods, brought on in part by Egypt’s shifting place in the global

market, has transformed the urban religious consciousness.

Full text of the article: Political Economy of Religious Commodities