As a Holocaust historian and educator, I am often asked, “Why did no one resist?” Fortunately, there was considerable resistance, from many quarters and in many forms. This becomes more visible when we break free from narrow definitions of “resistance” —such as the notion that only armed struggle qualifies as resistance. On November 16 and December 3 UNC Charlotte’s School of Music and the university’s Center for Holocaust, Genocide & Human Rights Studies will host two events that highlight a particularly striking and powerful form of defiance to Nazism: cultural resistance.

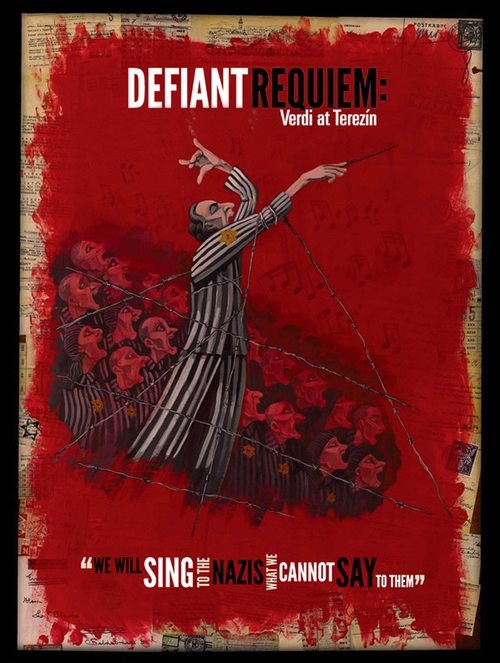

The concert “Defiant Requiem: Verdi at Terezín” will be performed on December 3 at UNCC’s Robinson Hall. The concert will be preceded by a screening of a documentary on the same theme on November 16 at the university’s Center City location.

The Nazis used their infamous camp Theresienstadt (aka Terezín), forty miles north of Prague, as a “model” camp that they claimed was humane, a ruse that some outsiders accepted. To buttress this charade, the Nazis transported large numbers of artists and musicians to the camp. Within strict limits—limits that the prisoners challenged and expanded—some artistic expression was allowed, and for propaganda purposes even encouraged.

In 1941 Rafael Schächter, already an accomplished young Czech conductor, was arrested and sent to Terezín. He managed to recruit 150 prisoners and teach them Verdi’s Requiem under near-impossible conditions: learning by rote in a dank cellar using a single score, and holding semi-clandestine rehearsals after long days of forced labor.

They performed the piece sixteen occasions for fellow prisoners. A final, infamous performance occurred on June 23, 1944 before high-ranking SS officers from Berlin and officials of the International Red Cross.

Schachter collaborated with the famed pianist and composer Gideon Klein, among others. Klein would also perish during the Holocaust.

The concert/drama that will be performed on December 3, “Defiant Requiem: Verdi at Terezín,” is a multi-media production two hours in length. “Defiant Requiem” was created by Maestro Murry Sidlin and has been performed around the world. From the production’s website:

The concert/drama presents a complete performance of Verdi’s Requiem combined with elements of on-stage drama, video interviews and authentic film from the era.

The performance begins with cacophony of sounds representing the vast variety of performances presented at Terezín during any week. At the sound of a piercing train whistle all music stops and the Requiem begins. Film excerpts include moments from the propaganda film “The Führer Gives the Jews a City.” To achieve authenticity, movements of the Requiem begin with an out of tune piano and evolve into the ideal of the orchestra.

The real heart of this story is the life-affirming harmonious effect brought about by great music which offered hope, courage, dignity and assurance to all who sang or heard it, through the expressions of faith, justice, love and compassion found in the mass.

Murry Sidlin came upon this story by chance. Browsing through a book in a bookstore in Minneapolis—he was on the faculty at the University of Minnesota’s School of Music—Sidlin alighted upon a brief reference to the Requiem performances in Theresienstadt. As he explained in a 2008 profile:

I thought to myself, “My God,” and then all the implications of this started to strike me: Verdi’s Requiem in a concentration camp—“Recruited singers” was all it said—who were these singers? and this conductor? why the Verdi Requiem in that place? Why did a choral conductor who was in prison for being Jewish recruit something like 150 singers to learn by rote a choral work that is steeped in the Catholic liturgy with a chorus that was 99 percent Jewish? That was the genesis of the project.

Sidlin, whose paternal grandmother and her family where killed in a Latvian ghetto, contacted some Holocaust experts, but they could not provide much helpful information about Schächter and his co-conspirators. It was when he began to contact survivors, as the Defiant Requiem Foundation’s site explains, that the story began to unfold:

One morning at 4.a.m., Sidlin bolted out of bed with a thought and combed the text of Verdi’s masterpiece: “Who shall I ask to intercede for me, when even the just ones are unsafe…Give me a place among the sheep and separate me from the goats…Nothing shall remain unavenged…That day of calamity and misery, a great and bitter day.”

“I could see that almost every line of the Mass could have a different meaning as a prisoner,” detected Sidlin. ‘Deliver me O Lord’ for them meant liberation. Nothing remaining unavenged was certainty of punishment for their captors,” he said. When Sidlin checked with the survivors they confirmed his insight into why they were so drawn to the work.

A survivor named Marianka May, for example, told Sidlin that as he assembled and prepared the musicians, Schächter started using words like “defiant”: “This is our way of fighting back—we take the high ground—we stand above—we have a vision of high art—the Verdi Requiem is the pinnacle of defiance.” And Schächter also said to them a number of times: ‘We can sing to the Nazis what we cannot say to them’—that was the essence, that was the message behind the Verdi.”

Members of the Prague Symphony Orchestra, Prague Philharmonic Choir, and the Kühn Choir of Prague take stage for June 2013 performance of the Defiant Requiem in Prague’s St. Vitus Cathedral. Photo credit: Josef Rabara

On November 16, two weeks before the concert performance, the School of Music and the Holocaust-studies center will show a documentary film, Defiant Requiem, at UNCC’s Center City location. The 80-minute film employs “testimony provided by surviving members of Schächter’s choir, soaring concert footage, cinematic dramatizations, and evocative animation. This unique film explores the singers’ view of the Verdi as a work of defiance and resistance against the Nazis.”

Susan Cernyak-Spatz survived Theresienstadt as well as Auschwitz, and at the age of 95, after having taught German for many years at UNC Charlotte, remains a visible and vibrant presence in the community. Dr. Cernyak-Spatz knew Gideon Klein and other artists in Theresienstadt, and she will speak at the November 16 event in Uptown Charlotte, which is free. More than once in the last year, Susan has expressed to me her concern over the rise of nationalism and fascism, which “remind me of things I saw in Berlin and Vienna” in her youth.

Maestro Murry Sidlin will conduct and preside over the December 3 concert at UNCC. Tickets are inexpensive ($8-10) and are available here.

Sidlin has said, “my own objectives were simple: I am attempting to give Schächter the career he was prevented from having; and I want everyone who learns of the commitment to the ‘high ground’ taken by the conductor and chorus to associate them always with the Verdi score. Then, there are the most important issues: the value of life and living, the depth they all achieved in understanding the music—returning to Verdi’s core, and the psychological, emotional, and physical effects of the music, and the hope it brought them. That’s it.”

Information about the November 16 film-showing

Information about the December 3 concert

This article was also published on the blog site of WDAV, Davidson’s classic music radio station.