In this class and in my previous blogs, discussions have largely revolved around the dangers of heritage tourism and the negative impact it often has on local communities. In an earlier blog about the tourism industry in Palm Springs, for example, I discussed the ways in which the history of the indigenous, local culture is exploited in order to promote the economic and political interests of those in power. In this week’s readings, one common theme is that of identity and in particular how outside interests use tourism to shape the identity of local communities, oftentimes at their expense. In “Novel Tourism: Nature, Industry, and Literature on Monterey’s Cannery Row”, Connie Chiang examines the process by which the restoration of Cannery Row was carried out, and how the local and economic interests transformed the identity of Monterrey from a small, sleepy fishing town into a tourist attraction in and of itself. In “Stumbling toward the Millennium: Tourism, the Postindustrial World, and the Transformation of the American West”, Hal Rothman goes further, claiming that the struggle between the interests of local communities who wish to maintain their authentic cultures and the economic and political interests that wish to make money off of these communities is a battle over their soul.

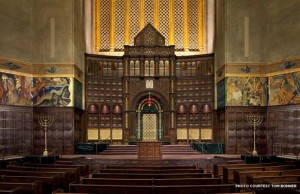

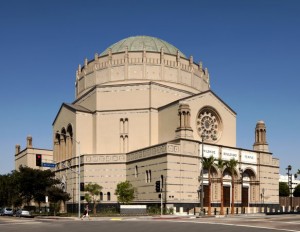

These articles and assertions have forced me to ask the question: Are there examples of heritage tourism in which both local and economic/political interests align? One such venue might be religious heritage tourism, or tourism that is united by a strong, local religion whose currency is less about money than it is about belief and community. An example I would propose is that of the Wilshire Boulevard Temple, which serves as the third home of the Congregation B’nai B’rith, the oldest Jewish congregation in Los Angeles. The congregation purchased the property in 1921 and the Temple itself was dedicated in 1929. Some of the most distinctive and historical aspects of the Temple include its theater-type design, a Byzantine dome (which spans 100 feet and rises approximately 140 feet above street level), extensive use of stained glass windows and marble columns, and most amazingly murals commissioned by Warner Brothers murals depicting 3,000 years of Jewish history.

Despite the building’s designation as a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument in 1973 and listing in the National Register of Historic Places in 1981, by the early 1990’s the Temple was in disrepair. The stunning murals, for example, were cracked and in need of conservation, while part of the dome had cracked and fallen due to water damage. In 2004, the Temple’s Board of Trustees decided to restore the Temple. Mostly due to the efforts of the local Jewish community, 47.5 million dollars were spent from 2011-2013 to restore the Temple which reopened its door in September 2013.

If Rothman is right, and if the struggle for authenticity and identity is a battle of the soul of the community, then one could argue that the community has won. The restoration of the Temple is a restoration of the religious and cultural center of the Jewish community. If the Temple had been destroyed and sold, the community would have most likely deteriorated rapidly; many would have had to move to a location close to another Jewish temple. With the restoration of the Temple comes a sort of restoration of the larger community and consequently the preservation of its Jewish identity. In addition, the purpose of the entire project was to restore the Temple to the state to which it was originally built. What better way to restore the authenticity of the site than to restore the history to which it’s attached?

All of this would be great if the story ended here. However, it has not. Whatever the reason, whether it be ambition or a genuine desire to help others, Jewish leaders have decided to go beyond the restoration of the Temple and look now to raise additional funds to create an entire campus. Now, the restoration is one part of a major 10-year, $150 million plan that includes a full renovation and expansion of the Temple campus to provide new educational and community services. This includes two school buildings, a new structure providing social services such as a food pantry and health services, athletic facilities, and parking; and landscaped areas throughout the campus. It is at this point that the local Jewish community is in danger of losing its soul, because in order to raise the $150 million outside funding is required. In fact, one could argue that this has started to happen already. Suddenly, the messages coming from the Temple have changed. Where before the focus was on the Temple and preservation of its history for the Jewish community, now the focus is on how great the Temple will be for everyone involved. According to one source, the Temple “is not only a symbol of religious vitality for Jews, but it will serve as an important resource for the immediate neighborhood, which is predominantly Korean and Latino” (Los Angeles Conservancy). While this might sound great to Jewish leaders and the business and political backers who are now necessary to help fund the project, what does it mean to the Korean and Latino communities that it might displace? Won’t this move by Jewish leaders lead to a new struggle, this time over identities other than the Jewish one?

Clearly, there are situations in which community, business and political interests in local tourism align. In the example of the Wilshire Temple, funding was internally organized and focused on preserving Jewish heritage and culture. However, once additional outside funding was required, a kind of ideological and spatial battle over the soul of the Temple and surrounding community commenced. Perhaps what they’re saying is true. Perhaps the additional construction will prove to be of huge benefit to the people in the community. However, the repression of local Hispanic and Korean identities into one that is primarily Jewish for me causes concern that the battle for authenticity and identity have just begun.

Sources:

Chiang, Connie Y. “Novel Tourism: Nature, Industry, and Literature on Monterey’s Cannery Row.” The Western Historical Quarterly (2004): 309-329.

Rothman, Hal K. “Stumbling toward the Millennium: Tourism, the Postindustrial World, and the Transformation of the American West.”California History (1998): 140-155.

Walser, Lauren. (March 30th, 2015). PreservationNation Blog. Retrieved April 6th, 2015 from http://blog.preservationnation.org/2015/03/30/photos-wilshire-boulevard-temple-restoring-a-1929-landmark/#.VRrsXE3wsh5

Wilshire Boulevard Temple. Los Angeles Conservancy. Retrieved April 6th, 2015 from https://www.laconservancy.org/locations/wilshire-boulevard-temple

![00081622[2]%20-c%201932](http://pages.charlotte.edu/nmaximov/wp-content/uploads/sites/707/2015/04/000816222-c-1932-300x229.jpg)

umpy, however. Initially, the plan was to run the train as many as nine roundtrips a day, with stops along the route. Many residents of the towns located on the rail line and some of the biggest vintners, including Robert Mondavi, however mounted protests against the rail line. In a political showdown, Mondavi as well as some local businessmen and representatives forced additional regulations on DeDeoenico’s trains, and as a result 9 stops became 2 or 3 and stops were prohibited. And that’s what’s fascinating about this story. Usually, local business leaders are supportive of the tourism industry. Theoretically, the wine train would bring in more tourists, the tourists would spend their money in these towns or at these vineyards, and, the argument goes, the local economies would prosper. In this case, however, local leaders went to great lengths to protect not the authenticity of a heritage site or their own economic interests but, in their view, the best interests of their communities. As former St. Helena mayor Lowell Smith put it, “we have fought very hard in this community to not become a tourist mecca or tourist destination per se…we don’t want to be a Disneyland” (Doyle, 2002, pg. 1).

umpy, however. Initially, the plan was to run the train as many as nine roundtrips a day, with stops along the route. Many residents of the towns located on the rail line and some of the biggest vintners, including Robert Mondavi, however mounted protests against the rail line. In a political showdown, Mondavi as well as some local businessmen and representatives forced additional regulations on DeDeoenico’s trains, and as a result 9 stops became 2 or 3 and stops were prohibited. And that’s what’s fascinating about this story. Usually, local business leaders are supportive of the tourism industry. Theoretically, the wine train would bring in more tourists, the tourists would spend their money in these towns or at these vineyards, and, the argument goes, the local economies would prosper. In this case, however, local leaders went to great lengths to protect not the authenticity of a heritage site or their own economic interests but, in their view, the best interests of their communities. As former St. Helena mayor Lowell Smith put it, “we have fought very hard in this community to not become a tourist mecca or tourist destination per se…we don’t want to be a Disneyland” (Doyle, 2002, pg. 1).

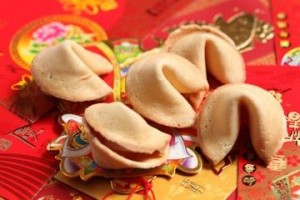

Chinese community is mentioned in their advertisements, walking tours continue to emphasize the stereotypical views that are often found in the media. For example, a company called Viator offers walking tours of Chinatown that encourage tourists to “sample fortune cookies…step inside an herbal pharmacy….and visit an authentic Buddhist temple” (Viator). The same walking tour also claims to provide “the inside scoop” of Chinatown’s “private clubs and secret societies” (Viator). In an interview by Bek Phillips (2013), Philip Choy, author of the book “San Francisco Chinatown”, sees this ‘inside scoop’ as a means of promoting

Chinese community is mentioned in their advertisements, walking tours continue to emphasize the stereotypical views that are often found in the media. For example, a company called Viator offers walking tours of Chinatown that encourage tourists to “sample fortune cookies…step inside an herbal pharmacy….and visit an authentic Buddhist temple” (Viator). The same walking tour also claims to provide “the inside scoop” of Chinatown’s “private clubs and secret societies” (Viator). In an interview by Bek Phillips (2013), Philip Choy, author of the book “San Francisco Chinatown”, sees this ‘inside scoop’ as a means of promoting Chinatown as “a dark, sinister place” in order to earn money from unwitting tourists. In fact, during the interview Mr. Choy points out that the only authentic part of the pagoda of the building under which they stood were the colors; the pagoda itself was inauthentic.

Chinatown as “a dark, sinister place” in order to earn money from unwitting tourists. In fact, during the interview Mr. Choy points out that the only authentic part of the pagoda of the building under which they stood were the colors; the pagoda itself was inauthentic.