A thesis is basically the argument of your paper. Used properly, it also helps to structure your paper. That’s why professors are always looking for a strong, clear thesis. I think we understand that. But the problems come in when we actually have to write it and stick it somewhere in our paper. Let’s talk about a few ways to write a thesis.

1. Basic – A,B, and C. When we first started writing five-paragraph essays (don’t knock them – I still use them), we learned that the five paragraphs are the intro (including your thesis), three body paragraphs containing a supporting point each, and a conclusion. (Still a great way to write a paper – three sticks in the human brain). The thesis became pretty easy after that. You come up with an argument and then tell us your supporting evidence. For example: ARGUMENT – Dogs are awesome. EVIDENCE – They’re cuddly, they like to chase sticks, and they wag their tails. THESIS – Dogs are awesome because they’re cuddly, they like to chase sticks, and they wag their tails. Bam. Done. I love this method, but many professors may be looking for something a little more on a higher level.

2. Thesis Wheel. This is my current method of choice. I recently learned about it AND IT’S AWESOME. I can’t believe I went through high school and college without knowing about and using it. —rant now completed— The best way to explain this is to draw it out, so there will be pictures!

First, write down your topic in the middle of the drawing area.

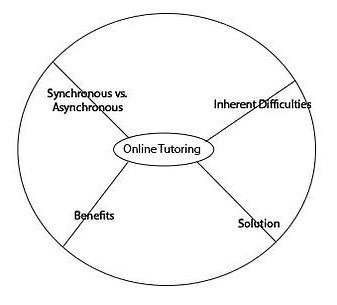

Here’s where the metaphor comes in. Just like a real wheel needs spokes to connect the rim and hub and support the rim, so does your argument. Your supporting evidence supports the main argument and becomes part of the thesis.

Returning to our example, we then ask ourselves “How do each of these points relate to each other and my topic?” For example:

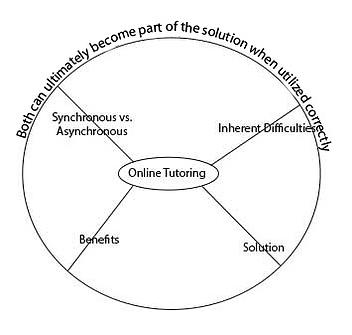

Synchronous and asynchronous tutoring have different benefits and inherent difficulties, but both can ultimately become part of the solution when utilized correctly.

Once we have this general relationship down, we find the argument part of the thesis. In the example, it is “both can ultimately become part of the solution when utilized correctly.” We can tell it’s an argument because someone could disagree with the statement.

Going back to the picture, the argument goes around the outside rim.

This iteration may not be your final version, but it’s a good start and helps you get organized while writing. This particular example was taken from a graduate level paper and the final thesis ended up being:

While there are some drawbacks to both synchronous and asynchronous tutoring, the benefits of helping our clients be comfortable with technology and of serving off-campus clients certainly outweigh the problems. We can mitigate any drawbacks by using alternative programs for synchronous tutoring and having tutors be aware of the difficulties inherent in online tutoring to work through them.

Theses are important. They help structure your writing and let readers know what you’re going to be saying. Another great explanation of the thesis wheel can be found in Before the Outline: The Writing Wheel by Colleen Rae. (Found on JSTOR here: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27558174?seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents)

Good luck and happy writing.