I held a screening of Thin Ice: The Inside Story Of Climate Science on Earth Day in April 2013, the day the film was released. The response from the students was good – they liked seeing Earth scientists working on complex data collection related to improving our collective understanding of the Earth system.  Based on a written survey I asked many to fill out, I would say that the most general concern was that Thin Ice did not show enough data analysis – a great initial exploration into climate data is the National Academy of Sciences documentary on youtube called Climate Change: Lines of Evidence. I personally really appreciated the work of the Thin Ice film makers in showing not only how cohesive seemingly disparate problems in Earth sciences actually are, but also how enthusiastic Earth scientists are about their work. This enthusiasm, this love of their world and trying to understand it, is in my experience “the norm” amongst scientists studying some aspect of the Earth, whether that research is about the climate or climate change or weather or whatever (Earth sciences is a big topic). We love actively trying to solve these mysteries and understand how the physical world works. So I heartily recommend Thin Ice to anyone thinking about majoring in Earth Sciences or Meteorology or Geology or Geography.

Based on a written survey I asked many to fill out, I would say that the most general concern was that Thin Ice did not show enough data analysis – a great initial exploration into climate data is the National Academy of Sciences documentary on youtube called Climate Change: Lines of Evidence. I personally really appreciated the work of the Thin Ice film makers in showing not only how cohesive seemingly disparate problems in Earth sciences actually are, but also how enthusiastic Earth scientists are about their work. This enthusiasm, this love of their world and trying to understand it, is in my experience “the norm” amongst scientists studying some aspect of the Earth, whether that research is about the climate or climate change or weather or whatever (Earth sciences is a big topic). We love actively trying to solve these mysteries and understand how the physical world works. So I heartily recommend Thin Ice to anyone thinking about majoring in Earth Sciences or Meteorology or Geology or Geography.  You may not work with ice cores or ocean-based research or even climate models, but you will have the chance to work with a group of highly dedicated people on problems that are interesting and sometimes poorly understood. Let your passion lead you!

You may not work with ice cores or ocean-based research or even climate models, but you will have the chance to work with a group of highly dedicated people on problems that are interesting and sometimes poorly understood. Let your passion lead you!

Thin Ice the movie is available for mp4 download for only $10 through June 15 and you can watch from any device that plays mp4s. I will almost certainly screen Thin Ice in the Fall and Spring semesters of the upcoming academic year in my courses (Global Environmental Change and Applied Climatology). I am planning on buying another movie that visualizes change in a much different way called Chasing Ice. I haven’t watched this one yet, but I’ve heard very good things about the sweeping and powerful images of ice melting away before our eyes as the globe continues to warm.

Why is ice the theme of both movies? Well, actually Thin Ice is more about the scientists studying climate and my understanding of Chasing Ice is that it documents the ice as it is now with the implication that the ice will not be this way in even another generation. So, two ice-themed movies, but much different messages. Buy the mp4 of Thin Ice or watch for my screenings announcements. I’m 90% sure I’ll screen Chasing Ice in at least one of my classes as well. Visualizing global warming and seeing what scientists do (and LIKE to do!) is really important.

The issue is getting a load of attention and, as Gillis wisely acknowledges, the analysis and studies in the peer-reviewed scientific literature will take a couple of years to “settle” on an answer. I agree. The public and policy makers and just about everyone wants to know the answer though so every publication or even statement about climate sensitivity will be intensely amplified. I’ve been reading about this issue myself, mostly as I prepare to bring the very current discussion into the classroom (

The issue is getting a load of attention and, as Gillis wisely acknowledges, the analysis and studies in the peer-reviewed scientific literature will take a couple of years to “settle” on an answer. I agree. The public and policy makers and just about everyone wants to know the answer though so every publication or even statement about climate sensitivity will be intensely amplified. I’ve been reading about this issue myself, mostly as I prepare to bring the very current discussion into the classroom (

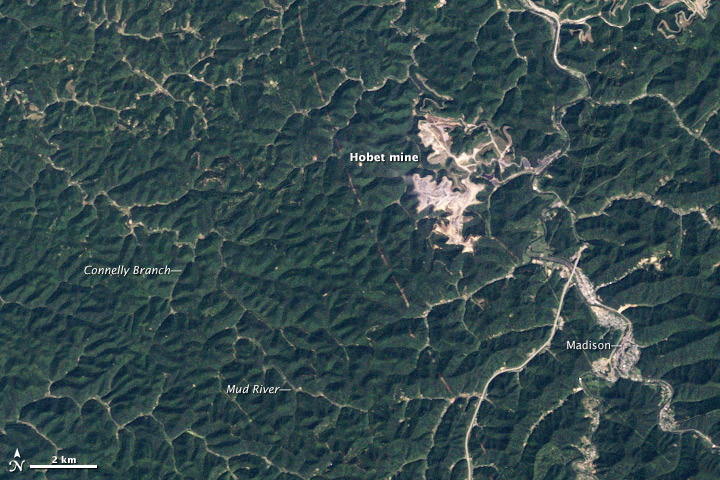

with another image of the same region in 2012

with another image of the same region in 2012  What do scientists do with this kind of imagery? Well, here is a the link to an amazingly clear image-animation of the

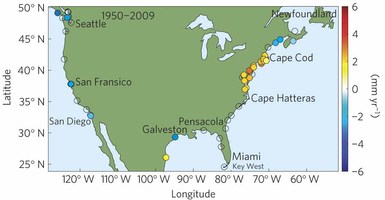

What do scientists do with this kind of imagery? Well, here is a the link to an amazingly clear image-animation of the  , which shows clearly that the West Coast and East Coast of the USA have already experienced much different responses to SLR. The data seems to be in line with the models, where a model projection is what is shown in the

, which shows clearly that the West Coast and East Coast of the USA have already experienced much different responses to SLR. The data seems to be in line with the models, where a model projection is what is shown in the