Climate Mitigation as Socio-Technical Transition: The Evolution of Eco-Cohousing in Tompkins County, New York

This post is another in our series presenting member research, focused primarily on the many insightful posters presented at this year’s conference.

by Robert Boyer

Ecovillages exist all over the world, in urban, suburban, and rural contexts. Some are very ‘low-tech,’ effectively eliminating electricity consumption and relying almost exclusively upon locally harvested and recycled resources for subsistence. Others are relatively ‘high-tech,’ using information technology and state-of-the-art materials to lower resource consumption. Some ecovillages are spiritually inclined while others are secular. Some are income-sharing ‘communes’ while others require members to meet economic needs independently. All ecovillages consist of members dedicated to ecologically low-impact lifestyles, and their diversity offers scholars and policy makers opportunities to explore innovative strategies to sustainable living around the world.

I chose to focus on ecovillages because I was dissatisfied with mainstream attempts to address global ecological crises. While cities and regions have embraced the rhetoric of sustainability, action on the ground has failed to even dent the most serious trends. So I decided to look to grassroots groups that prioritize low-consumption lifestyles and ask whether and which ecovillages might be able to inspire changes beyond their membership, in the mainstream.

The poster presented at the INSS meeting was an extension of my dissertation, which explores how (and where) experimental “ecovillage” communities are influencing mainstream processes of urban development. The study traces the journey of Eco-Village at Ithaca (Town of Ithaca, New York) from its early years as an idealistic vision to its current status as a source of new zoning codes in its home region.

The poster presented at the INSS meeting was an extension of my dissertation, which explores how (and where) experimental “ecovillage” communities are influencing mainstream processes of urban development. The study traces the journey of Eco-Village at Ithaca (Town of Ithaca, New York) from its early years as an idealistic vision to its current status as a source of new zoning codes in its home region.

Eco-Village at Ithaca’s eco-cohousing model did not begin as a “rational” or “mainstream” solution in the eyes of local policy makers. It had to overcome multiple practical, ideological, and regulatory hurdles to even exist where it settled. It violated zoning codes, for example, and its members had to work for a year with local officials to create a customized zoning category. The project has co-evolved with shifting political and regulatory landscapes that now favor climate mitigation, and county planners are drawing from the community’s lessons learned to help re-write zoning codes and permit more walkable, convivial urban development patterns. The poster outlines the four phases of development of Eco-Village, from idealistic vision to partner in urban development, and includes descriptions of the financial, legal, and ideological barriers, among others, that affected the development, as well as the support offered by new policy interests in climate change.

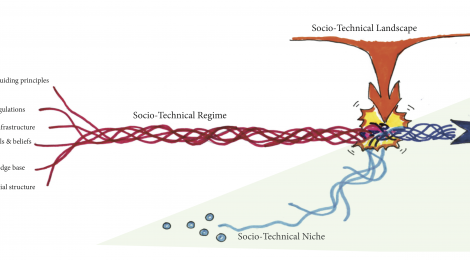

This project has renewed my faith in ‘mainstream’ urban planning professionals. While I began the project by focusing on grassroots initiatives, I discovered that grassroots projects cannot change the world independently. Skillful and entrepreneurial actors in the mainstream play an important role translating novel concepts from one context to another, and help facilitate structural change. My future work will focus more heavily upon these important “intermediary” actors.I am currently engaged in extending the theoretical model of this project (socio-techncial transitions) to broader applications of climate mitigation scholarship, specifically in the urban and regional planning discipline.

Robert Boyer is Assistant Professor of Geography at UNC Charlotte

This post was developed from Boyer’s poster and answers to interview questions by email. Please post any questions in the comments.